It’s been out for a month now but people are still buzzing over Dune: Part 2 (or Twone if you want to be annoying). Now seemed like a great time to remind folks of my previously published review of Dune: Adventures in the Imperium by Modiphius. If you like this, be sure to also check out Part 2 of the review and the very excellent Fall of the Imperium campaign which provides adventure material coinciding with the events in these two movies.

Whether you’ve read the books or just seen the movie (the recent one or one of the many other adaptations) it’s clear that Dune is a different sort of sci-fi story. There are many familiar tropes to hold onto, though most are fantasy instead of science fiction, and also some wonderfully original ideas that are fascinating to play out. Also a healthy dose of white saviorism which I recommend you axe in your stories…

With the sprawling universe that visionary author Frank Herbert created, the stories you can tell in the Dune RPG are not limited to the desert planet of Arrakis (though that’s definitely where the game’s interest is focused and the upcoming first sourcebook Sand and Dust will focus it even more). You can play a whole campaign of this and easily never set a foot on the desert world, and the universe is a big place so you have relatively free rein to make your own corner of it however you see fit.

Introduction to 2d20 and the Dune Universe

If you’ve read the books, or even watched the recent movie, you’re probably keenly aware that the universe of the Dune stories is vast and complicated. After some brief “What are RPGs?” business, the book starts with an overview of this universe that does a pretty decent job of covering the big points. The development of AI and the enslavement of humanity, the founding of the League of Nobles and the Butlerian Jihad to destroy the machine overlords, the development of the Great Schools to fill the gaps left by advanced computers, and the establishment of the Imperium. It discusses the Landsraad, CHOAM, the Bene Tleilax, myriad planets (including a lot about Dune itself, obviously), and plenty about assassins who are a big part of the stories. In all the 66-page second chapter goes over all of this in plenty of detail and is brimming with storytelling potential.

With such a long history, the game (like many franchise RPGs from Star Trek and Star Wars to A Song of Ice and Fire) makes an effort to support different eras of play so that you can pick your favorite: games set during the Butlerian Jihad against the machines, games set during the Reconstruction when the Great Houses are established, the Imperium which is the setting for the first novel and the movie, the Ascension of Muad’Dib which happens directly after the events of Dune, the era of the God Emperor which is a generation after Dune, the Scattering era after the wheels start to come off, and the Age of the Enemy when an existential threat attacks the exhausted Great Houses. In practice, most of the information is framed around the time when Paul Atreides lives but there are references throughout for folks who want to expand their story into other eras.

As a Modiphius product, Dune utilizes their in-house 2d20 system. It’s always interesting to see how a game system shifts to accommodate different settings, tones, and objectives. I’m most familiar with the 2d20 system from Modiphius in the Star Trek Adventures but I’ve read through the books for Infinity, Dishonored, and Conan and I’m eager to see the final version of the upcoming Achtung! Cthulhu rules (the Call of Cthulhu version was great and this one looks to be just as good). I won’t go into the basics of the 2d20 system since you can find that elsewhere on this blog but there are some neat changes to the system in Dune. Even though these are intended for Frank Herbert’s universe, I think they have immediate applications to any 2d20 game.

Agents and Architects

Right from the start, there are changes to the 2d20 system that’s unique (I think) to the Dune setting: Agent-level and Architect-level play. During the course of play you might be playing an Agent of your House, getting your hands dirty in a fight or leading a tense negotiation yourself. This is like a lot of RPGs, one character as a player’s avatar, but with the sweeping politics of the Dune universe there’s also the option for Architect-level play. In this you are using your character’s stats to direct and command other characters to accomplish things that you aren’t present for. From your family’s estate you have spies, soldiers, and diplomats across the stars doing things in dozens of different locations and then you reap the results. This could be ported over to Star Trek as a Starfleet admiral or Klingon general, to Conan as a sovereign issuing orders throughout a realm, or to Infinity as a director of some faction engaging in the rivalries and wars of that universe.

Increased Role of Traits

In all 2d20 games there are traits which your character has to establish some of their details. You might be familiar with traits from Star Trek Adventures which might be Vulcan or Prosthetic Limb, kind of basic stuff. The game then has distinctions for more involved characteristics like Always Dissecting a Problem or Human Ways Are Strange to Me. Most 2d20 games (including Conan and Infinity), however, have just traits and then split the difference between very basic and very involved.

Dune is this way and has traits like these but they’re more systematic than I’ve seen in other 2d20 games (there are also drives that work like STA distinctions, but that’s familiar ground). You typically have two traits: one that is your title or role (“Heir to House Lessana” or “Veteran Swordmaster”) and another that is about your personality (“Careful and Disciplined” or “Brash and Vengeful”). If you have an affiliation outside of your House (such as membership in a Great School or maybe even a secret loyalty to a rival House) then you might have a third trait. Scenes and locations also have traits to tell you what they’re all about. This is similar to how character aspects build your self in Fate or mysteries and identities create your story in City of Mist and it’s also what I’ve seen in playtests for the upcoming Achtung! Cthulhu 2d20 game.

This is also an approach to traits that’s immediately transferable to other 2d20 games since traits are free and only affect the game when it makes sense to. In your next Star Trek Adventures game, after players have written down their species as a trait, why not ask them for a trait that reflects their reputation on the ship or a trait as a tie to some group outside of Starfleet? It has almost no chance of derailing the game and is all but guaranteed to deepen your experience.

Assets and Conflicts

Violence is a big part of Dune stories but there are other arenas that characters regular clash in. I’m going to get into the different types of Conflict later in this review but one thing that does stand out is assets and how they factor into conflicts. There are many different types of assets (personal, warfare, espionage, and intrigue) and all of them factor into the game in different ways. They also have a Quality rating from 0 to 4 which impacts rolls made utilizing that asset, though most things in the game have a Quality of 0. For example, you might have a powerful turret cannon as part of your defenses which has Quality 1 or you might have an impeccable reputation for intrigue rolls that has a Quality of 2.

In simple terms, Quality makes assets easier to use (you can add defensive assets’ Quality to the Difficulty of attacks against you, you can more easily take out enemy assets with higher Quality offensive assets) and it also expands what can be utilized in the game. It applies to everything from weapons to stolen data to hidden assassins and it’s easy to import into other 2d20 games as well, especially given that a Quality of 0 is possible and even expected. In Star Trek Adventures, tools and items sometimes take a backseat which is not what happens in many onscreen Star Trek stories.

If you introduce the possibility that an engineer might have improved their tricorder to Quality 1 or that a recovered data cache might be Quality 2 when in a standoff with the Tal Shiar, this can give your players specific tools to use. This actually is already part of Star Trek Adventures since you have Advantages that can just be gifted instead of created with a roll or specific instances like Hidden X. Thinking of assets and Quality in the way that the Dune RPG does, however, helps to clarify how this game mechanic can improve your storytelling.

House Creation

It’s telling that the book presents you with the rules for creating noble Houses before it presents you with the rules for actual characters. We already saw some faction-level rules for the 2d20 system in the form of Klingon Houses for Star Trek Adventures but this take things a step farther. In the novels of the Dune universe, Houses are a bigger social and political force than planets or even armies. Everything comes down to the holdings and designs of the Great Houses in the Landsraad and it’s no different in the Dune RPG.

To start, you need to figure out what sort of House you’re making for your characters (or perhaps for adversarial NPCs). You could have a Nascent House with hardly any holdings of their own, a House Minor which serves a more powerful family but is perhaps rising itself, a House Major that controls an entire planet’s resources, and a Great House that commands several worlds and one of the most powerful positions in the universe. Picking a more powerful House has the trade off of giving the GM more Threat at the start of each session: 0 for Nascent Houses up to 3 per player for Great Houses.

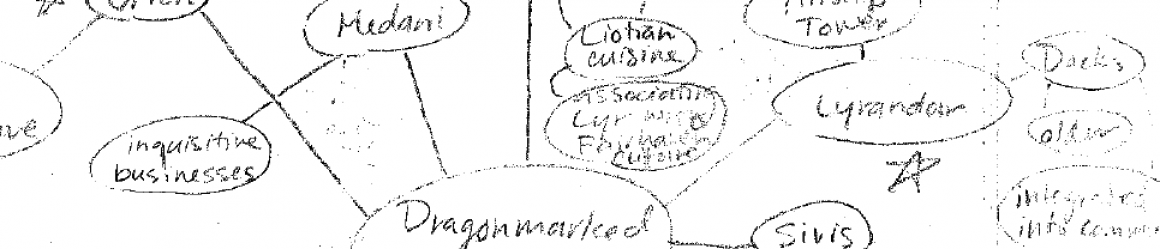

The power of Houses lies in their domains, areas of influence and business that the House can call on as assets in play. These can be primary or secondary and the number of domains depends on the rank of the House (you get two primary domains and three secondary as a Great House while a Nascent House has just one secondary). There are nine domains to choose from: artistic, espionage, farming, industrial, kanly (a polite word for “assassionation”), military, political, religion, and science. To further develop things, domains all have areas of expertise which explains just what the House excels at in that field. The book provides machinery, produce, expertise (training and managing people), workers, and understanding as areas of expertise to start, but you can make up other stuff if you like. These two elements combine to make forty-five different types of strengths that a House might have (more if you make up your own areas of expertise) so every House can excel at something. You can even pick the same doman-area combo multiple times with different specifics (such as Artistic-Produce as plays but also Artistic-Produce as musical pieces) and you have the whole primary and secondary domain thing to think of so there are literally hundreds of different choices for this.

Following these important choices, Houses should have homeworlds where their seat of power lies (for instance, House Atreides and House Harkonnen both ruled the planet Dune but their homeworlds are Caladan and Giedi Prime respectively), the banners and arms that signify the House, and traits the characterize how the House operates and makes it more like a character. Houses also have roles to fill, though these are narrative only and don’t have mechanical benefits like the roles in Star Trek Adventures: the ruler leads the house, their consort is a companion who cannot rule themselves (like Duke Leto’s wife who’s Bene Gesserit and so can’t rule), advisors give the ruler guidance, the chief physician keeps everyone healthy, the councilor represents the ruler to their people (and vice versa), the heir is the one intended to rule next, the marshal enforces the laws of the House, the scholar handles academic matters, the spymaster collects intelligence for the House, the swordmaster or weaponsmaster is combat trainer and bodyguard in one, the treasurer keeps the finances going, and the warmaster leads the armies.

Last, of course, the House needs some enemy Houses to establish its place in the Landsraad and also propel the game forward. More enemies emerge the more powerful a House gets so rank determines how many enemy Houses you should write up (Nascent Houses have no enemies, for instance, while Great Houses have several very powerful enemies). Tables help you randomly determine how strong the hatred between the Houses is (are they just grumpy with each other or actively sending assassins to kill them?) and where it comes from (competition in a domain? some ancient feud from a thousand years ago? former bonds of fealty now broken?). Again, these combine to make a huge number of possible histories between Houses (four hatred results and ten reasons so sixty in all) before you even start considering the specific details. Tons of room for creating a unique house for PCs or adversaries!

Conclusion

We’ve really just dipped our toes into the water (sand?) of the Dune RPG but that’s enough for Part 1. Next time I’ll be looking at the individual characters of the game and how to make them as well as adversaries you might face and all the different arenas of conflict that Dune offers to tell dramatic and tense stories.